Leany on Life -- August 2017

I may not agree with your opinion, but I will defend to the death my right to ridicule it.

Leany home

|

Articles

|

Chronicles

|

Prostitution Arrests

|

Who is Frank Leany?

|

Libotomies

|

Past Blogs

January 2018October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

April 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

October 2016

August 2016

July 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

March 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

November 2015

October 2015

September 2015

August 2015

July 2015

June 2015

May 2015

April 2015

March 2015

February 2015

January 2015

December 2014

November 2014

August 2014

July 2014

May 2014

April 2014

March 2014

February 2014

January 2014

December 2013

November 2013

October 2013

September 2013

July 2013

June 2013

May 2013

April 2013

March 2013

February 2013

January 2013

Meanwhile, over in an Alternate Universe

Click Here to go to Blog Below

(Best viewed with a mind not clouded by the Kool-Aid)

Forever Wednesday

Billy Shakespeare once said "There is nothing new under the sun." True it is.I really don't need to post new material every Wednesday; I've posted enough to show you the correct viewpoint on whatever comes up. But even if the news is always the same, you like to have a fresh clean newspaper with breakfast every day.

Clicking the "Billy's Blog" button to the left will deliver a fresh old post right to your screen. No matter how old it is, it will probably be relevant to what's happening today.

Today's Second Amendment Message

It can be discouraging to look around at who's running the show these days and wonder "Where have all the grown-ups gone?"

Take heart. There are still some people who are not drinking the Kool-aid. Here's where to find them. I would suggest going down this list every day and printing off the most recent articles you haven't read to read over lunch.

Michelle Malkin

Michelle Malkin is a feisty conservative bastion. You loved her book "Unhinged" and you can read her columns here.

Ann Coulter

Ann posts her new column every Thursday, or you can browse her past columns.

George Will

What can you say? It's George Will. Read it.

Charles Krauthammer

posts every Friday. Just a good, smart conservative columnist.

If you want someone who gets it just as right, but is easier to read, try

Thomas Sowell,

who just posts at random times.

Jonah Goldberg seldom

disappoints.

David Limbaugh carries on the family tradition.

Jewish World Review has all these guys plus lots more good stuff.

Or you can go to radio show sites like

Laura Ingraham's

or

Glenn Beck's

or

Rush Limbaugh's..

If you'd like you can study The Constitution while you wait.

Then there's always TownHall.com, NewsMax.com, The Drudge Report, FreeRepublic.com, World Net Daily, (which Medved calls World Nut Daily), News Busters, National Review Online, or The American Thinker.

For the Lighter Appetite

If you have to read the news, I recommend

The Nose on Your Face, news so fake you'd swear it came from the Mainstream Media.

HT to Sid for the link.

Or there's always

The Onion. (For the benefit of you Obama Supporters,

it's a spoof.)

Dilbert.

Dave Barry's Column

Daryl Cagle's Index of Political Cartoons

About half of these cartoonists are liberal (Latin for wrong) but the art is usually good.

(Fantastic, if you're used to the quality of art on this site.)

Another Cagle Index

Townhall Political Cartoons

In case you want cartoons that are well-drawn and don't make your jugular burst.

Or just follow the links above and to the right of this section (you can't have read all my archived articles already). If you have read all my articles (you need to get out more) go to my I'm Not Falling For It section.

Above all, try to stay calm. Eventually I may post something again.

The Litter-ature novel is here. I update it regularly--every time Rosario Dawson tackles me and sticks her tongue in my ear.

Understanding the 2012 Election

My Sister's Blog New!

Complete Orienteering Course Files

Things you may not know about Sarah Palin

What the hell kind of country is this where I can only hate a man if he's white?

Hank Hill

On This Day in History

Oh, wait . . . that's from an alternate universe

And the blah-blah-blog continues . . .

Refresh to get latest blog entry

Ideas, Good and Bad

8.22.17

My faithful imaginary readers might know that I like to amuse myself by making up fictitious stories. Just make-believe tales about people in the workplace doing things that no real person would do, completely out of my imagination, without reference to anyone I know or work with.

Here's a sample.

In an earlier life Frank had worked as a designer in the automated control valves industry.Automated control valves are very complicated systems that work within even larger complicated systems. Because of the dynamics of fluid moving through pipes careful engineering went into the placement and support of all the components. Every valve the company shipped had to have the location of the actual center of gravity marked on the valve.

As Frank was passing the assembly area he heard a clatter followed by loud swearing. He looked over where people were scrambling to pick up the pieces of the very expensive control valve that had just crashed into the workbench. The device used to determine the center of gravity of a valve involved hanging it precariously from a chain and adjusting a bar until it balanced.

Frank thought there must be a better way.

When he got back to his desk he sketched up an idea on a piece of paper. Throughout the afternoon he snuck some time in here and there to design his creation on the computer. That evening he stayed late after work just long enough to get the design into a version he could present to his boss.

The next morning Frank unveiled his creation to his boss, Bryan. Bryan was familiar with the time and trouble involved in the current way of measuring CG, and he was aware of more than one mishap with that operation, including one involving a worker getting injured. He praised Frank for his innovation and gave him permission to finish the design and build a prototype, as long as doing so didn't interfere with Frank's regular duties.

The company had an idea program whereby employees could be recognized and rewarded for ideas that helped the company. Bryan suggested that Frank submit his idea. If it worked it would save the company money and time, and increase safety, the stated goals of the idea program.

In the following week Frank finished the design, had a buddy in the weld shop fabricate the frame and convinced another friend in the R&D lab to rewire a couple of electronic bathroom scales to give the desired reading.

The guys in the assembly area gave the new method their stamp of approval and Frank submitted the idea.

After the committee reviewed the project Frank was given a cash award, part of which he used to take his buddies from the shop and his boss to lunch. The money was appreciated, but Frank also felt a sense of pride whenever he passed assembly and saw someone using his device.

To the right of reception desk in the lobby was a door leading into the administrative offices. Just on the other side of that door was the giant multi-function copy machine. Frank pushed through the door to go into the front offices and hit it right into Mr. Marks's cute little administrative assistant. "Sorry. I'm so sorry," he said.

"Oh, you're fine," she smiled. "I can usually get out of the way in time. Happens all the time.'

"That door really needs a window," Frank joked, and Marks's assistant laughed.

When Frank got back to his desk he thought "Why not?" He quickly typed up the idea, got his boss's approval, and submitted it to the idea committee.

About three weeks later Frank got a response from the idea committee. A window in that door would not do at all. Glass was a safety hazard (in a building with giant glass walls looking out onto the surrounding ponds and gardens) and besides, a window would break up the carefully crafted aesthetics of the front lobby.

Oh, well. He'd tried.

About a month later Frank was coming in to work through the front lobby. As he passed the receptionist desk to go to Engineering on his right he looked over and greeted the receptionist. Then he paused. There in the door to Administration, the door right next to the copier, was a neat rectangular window.

"Well, I'll be . . ." he snorted.

"What?" Mike Carr asked. He was on his way to Engineering, too.

Frank wagged his finger at the door. "I . . . not two months ago, I suggested that we put a window in that door."

Let me guess, Mike said. "It got shot down."

In response Frank shook his head, which Mike correctly understood to be an answer in the affirmative. "They said something like it messed up the look and feel of the place or something."

"That's Scott talking," Mike said. Scott Foster was the head of physical plant. Mike explained that he viewed part of his job as finding a reason to reject any ideas that involved his department. He figured that paying employees for their contribution was a big waste of money.

"Let me tell you a story." Mike put his arm on Frank's shoulder and guided him out of the lobby.

Out in the machine shop the power was run up in the ceiling, two stories above the concrete floor. This gave flexibility to move machines wherever they were needed by dropping a line anywhere. No need for a wall or pedestal or fragile floor outlet. Each main line ran down from an electrical box with a handle for shutting off the power.

Throughout the shop were scattered long 2x2 wooden sticks, with a metal rod in the end. The purposes of these was to reach up and shut off the power when needed. The poles could then be used to turn the power back on when whatever maintenance was done.

Mike Carr had submitted an idea to tie a rope to each handle, leaving it dangling down next to the power line. That way in an emergency anyone could pull the rope and quickly shut off the power. That would eliminate the need to try to find the pole and the dexterity required to guide it 16 feet up into a loop on a handle.

True to his form, Scott had rejected the idea. One of the reasons he gave was that the rope posed a safety hazard: if the rope were permanently attached someone could switch the power on when it was supposed to be locked out by pushing up on the rope.

"No!" Frank said.

"Swear to God, " Mike said.

"Wow. Oh, well, I guess, you know, how much would they have paid you for that idea anyway, right?"

"Doesn't matter," Mike said. "I submitted the story to Readers Digest. They ran it in All in a Day's Work and sent me a check for 600 bucks."

I'll Get to It

8.06.17

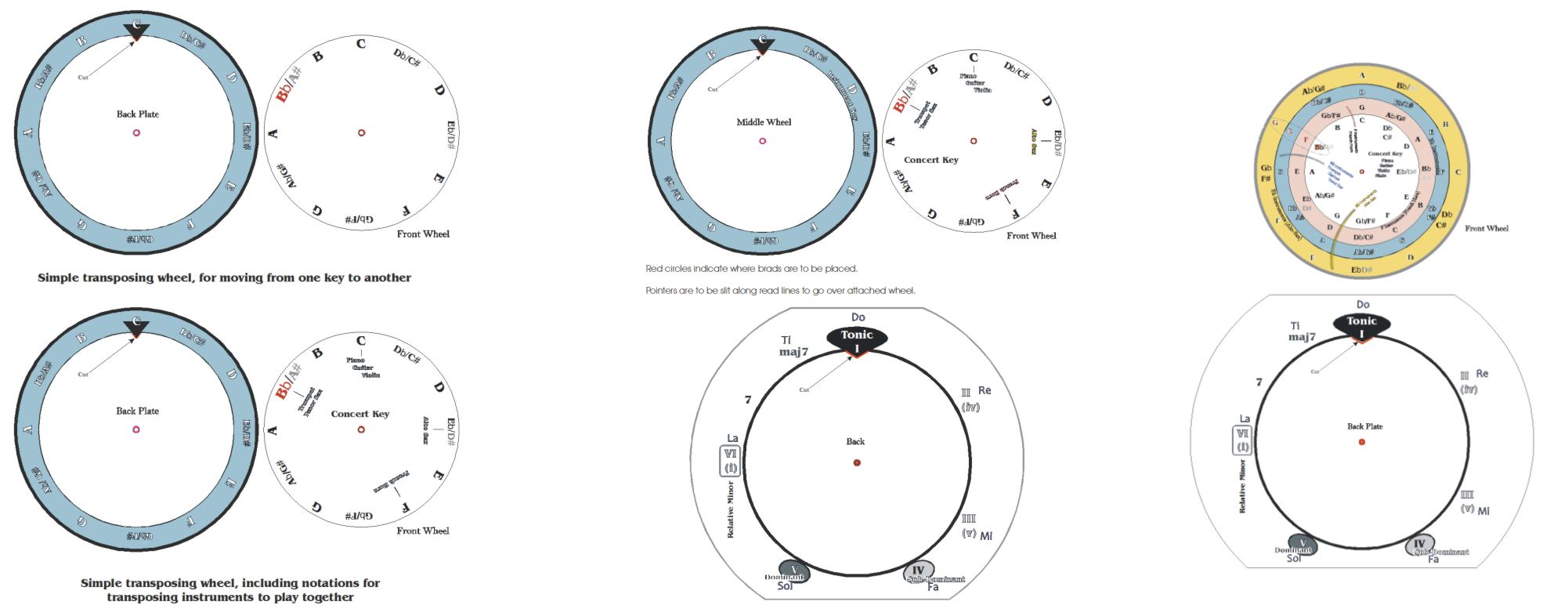

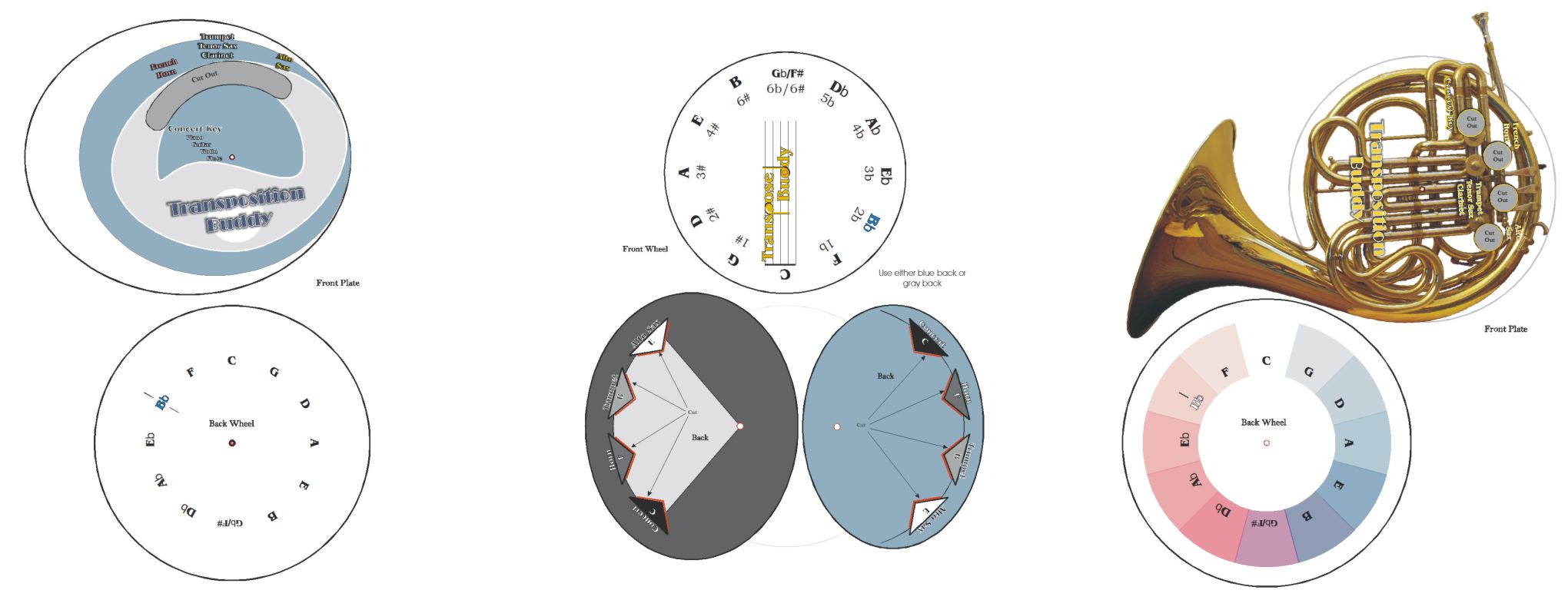

I know what you're thinking. You're thinking "Frank, why don't you turn all those little transposing wheels you've created into .pdf files that we can print off?"But I'm thinking. "Geez, how come my special fonts disappeared and the flat symbols show up as lower-case b, if they print at all, and why do the colors render differently in the PDF than when I print from the native software?"

And you're thinking "No excuses, Frank. We want to print stuff out on card stock and cut it out and put it together with brads and carry extra stuff around in our instrument case, instead of downloading free apps that do it better on a little phone we already carry."Give me a break, guys. Being irrelevant isn't as easy as it looks.

No Shortage of Buses

8.02.17

My faithful imaginary readers might know that I like to amuse myself by making up fictitious stories. Just make-believe tales about people in the workplace doing things that no real person would do, completely out of my imagination, without reference to anyone I know or work with.Well, I thought up another one today.

While it wasn't remarkable for Frank to be at his desk at 7:30, it wasn't standard practice either. But that morning he was there, a half hour early, and an hour before most of Carson's employees showed up.

At 8:06 Frank got a group text from Rudy, the field sales rep, asking

"You calling into meeting."

He replied that his calendar didn't show one, could he get the information to join the meeting.Larry and Carson each replied that they were coming.

Frank could only wait for the instructions. After all, Larry and Carson weren't there yet, either. As soon as they showed up he could just get on the call with them. He didn't know what else to do.

Frank was the first to acknowledge he wasn't a model employee. Well, maybe he was second to acknowledge it. Right after his boss, Carson.

Carson always told Frank was that he was doing a "fantastic" job. But he was quick to catalog Frank's failings to everyone else, then Frank heard it through the grapevine. What came through those channels gave some context to some of Carson's otherwise puzzling actions.

Frank had enough real failings that he didn't see the need for Carson to invent stuff to blame him for. But it fit with Carson's general habit of dramatizing reality--the guy would fabricate a story when the truth made better material. To Frank it seemed like extra work for no payoff.

After a couple of minutes with no response to his text, Frank made his way to Carson's office. By this time Carson was there, with Larry, sitting at the conference phone. When Frank walked in Carson said into the phone "Frank just barely got here."

Really, Carson? Not "Frank is here with us?" Not . . . something else?

"I don't have this meeting on my calendar," Frank said. A career of dealing with Dalton had taught Frank not to let himself get bent over in meetings.

Larry held his phone up pointing towards Frank. "You're right here," he said. "It says no reply."

"I don't know what to tell you," Frank said. "I didn't get any meeting invitation."

Frank was irked, but he figured he was being oversensitive. One little sentence clumsily spoken wasn't worth stressing over. It had already been a bad morning following a bad night in the middle of a horrible year. Whatever. Life goes on.

Frank mentioned the incident to Brandon after the meeting--"mention" being the French word for whining extensively. Then he went on with his day, always on the lookout for other things to be in a bad mood about.

Mid-morning Brandon poked his head in Frank's office. He told Frank he had apologized to Carson for not being at the meeting, explaining that he had never gotten an invitation and it was not on his calendar. Carson had replied "That's okay, you didn't really need to be there. We were just discussing the J-Pick."

Then he'd added "But Frank did. And he was late."

A career of dealing with Dalton and Allphin boiled over in Frank's mind. He was now operating from what John Goodman called a position of "Screw you." Only John Goodman might have used a stronger word.

Frank texted back to the original group that he had been here since 7:30 and the first he'd heard about the meeting was at 8:06 when Rudy texted. Then he e-mailed Carson that he would have joined from his computer that morning if he'd had the information, and pointed out that Carson and Larry weren't there at that point anyway.

Two minutes later Carson showed up in Frank's office door. "Hey, I guess I need to do a better job letting you guys know about meetings."

Frank didn't strictly adhere to John Goodman's policy. He didn't suggest that Carson could contact everyone on the conference call and retract his characterization of Frank dragging his slacker carcass in late to a meeting--a meeting that Carson himself was late to.

He just said "Yeah, I'm better equipped to attend meetings that I know about."

What the &#%* ever.

Click "Prev" below to go to earlier posts