French Horn Harmonics

What I Wish I'd Known When I First Picked up a French Horn

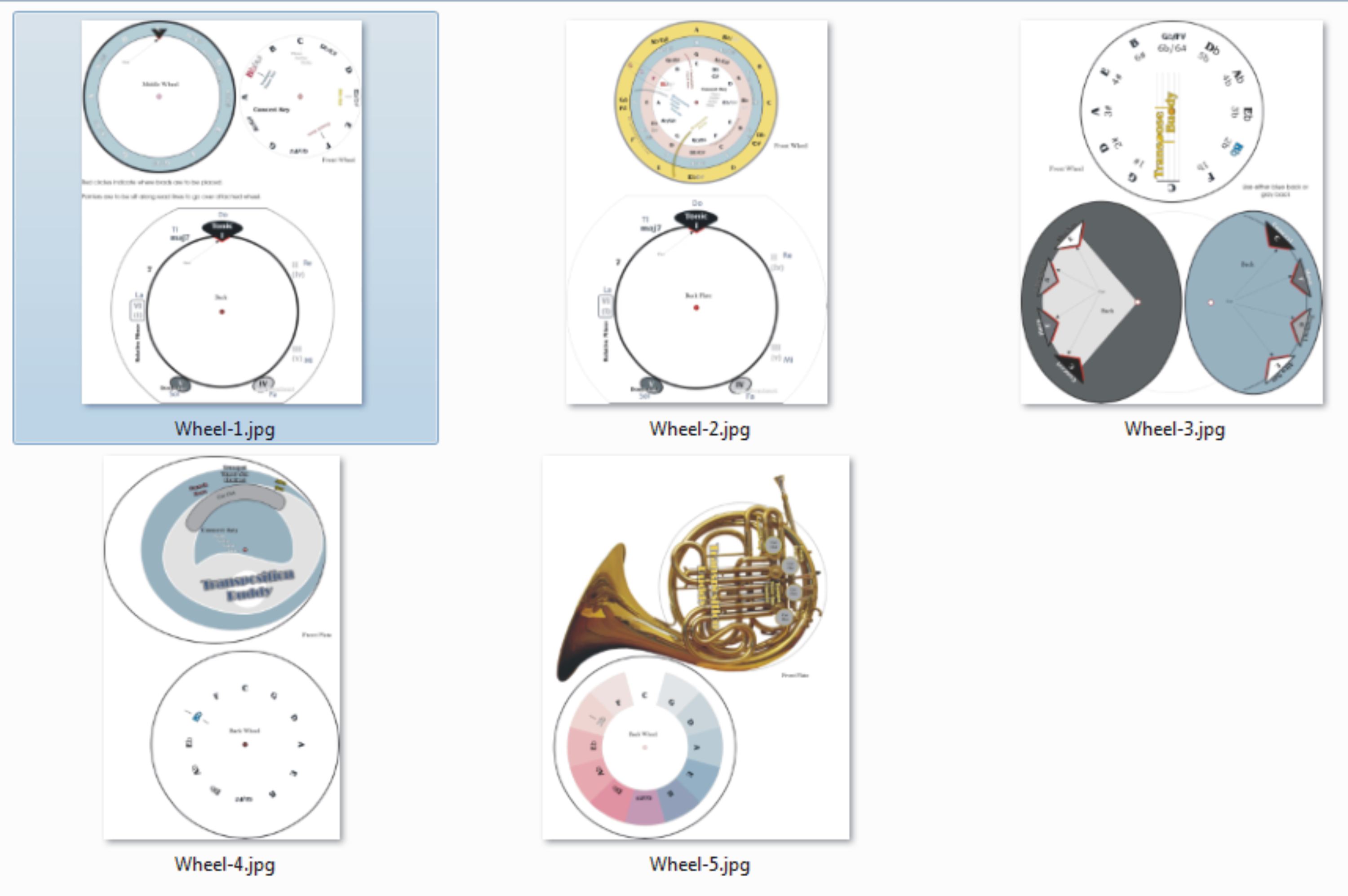

This page has some resources that might be helpful for horn playing and transposing. I've designed wheels that help me transpose and visualize the relationship of instruments in different keys. I've also created a movable graphic to explain why French horns misbehave the way they do with partials. I hope you find something useful.

French Horn Harmonics (Fingering) |

My Story |

The Missing (Brass) Link |

Transposing mnemonic |

Ramblings about Trombones and Stuff

Ugh, French horns! Amirite?

If you play the French horn, especially, if you're just starting out, you know how frustrating it is to make the right note come out of the thing. I hope this page helps you understand what's going on with that.There's a lot of verbiage on this page. Use the links above to navigate around to what's useful for you.

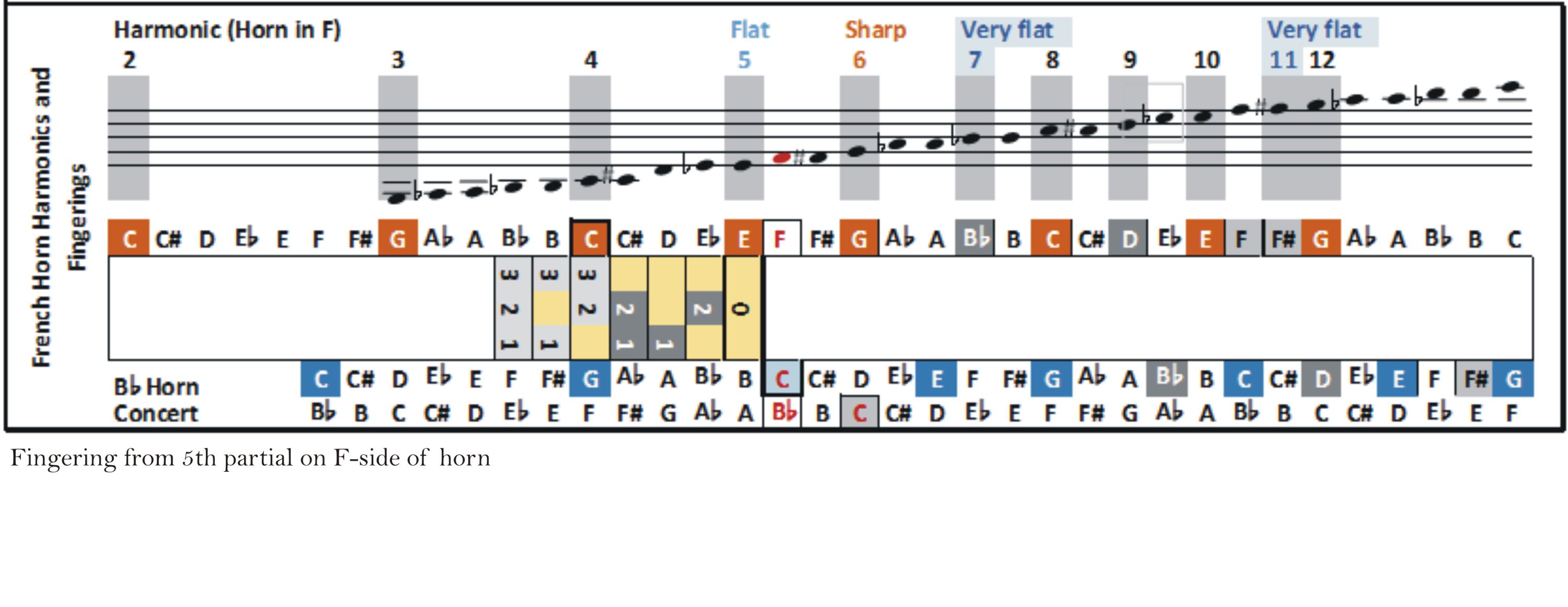

French Horn Harmonic Series and Fingerings

7.14.17

OrIllustrations

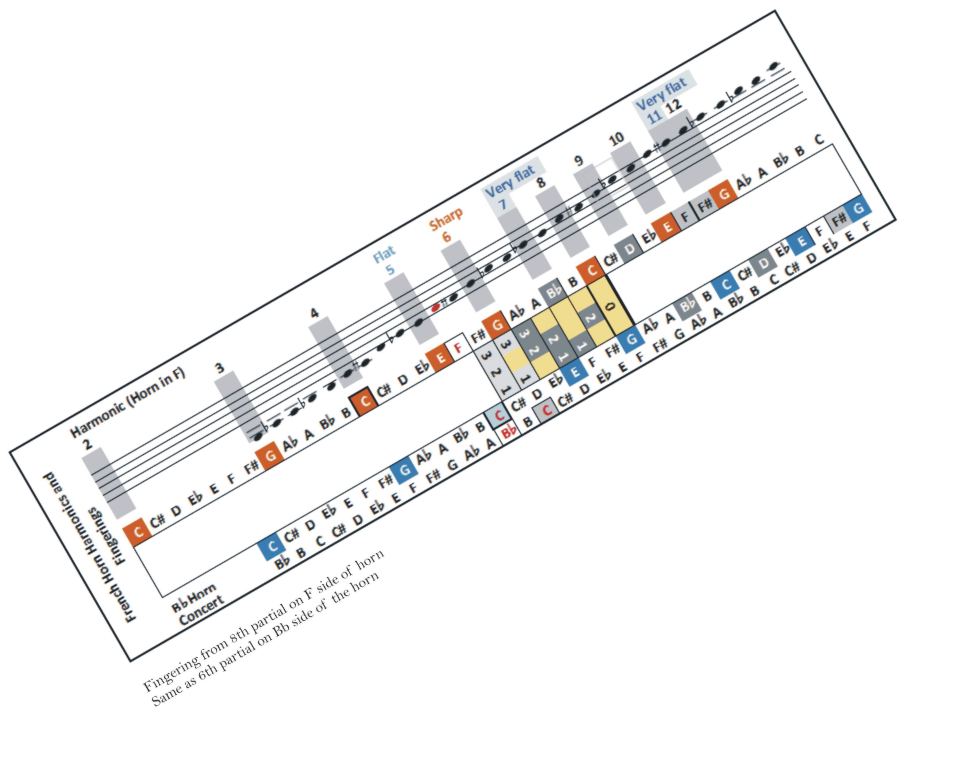

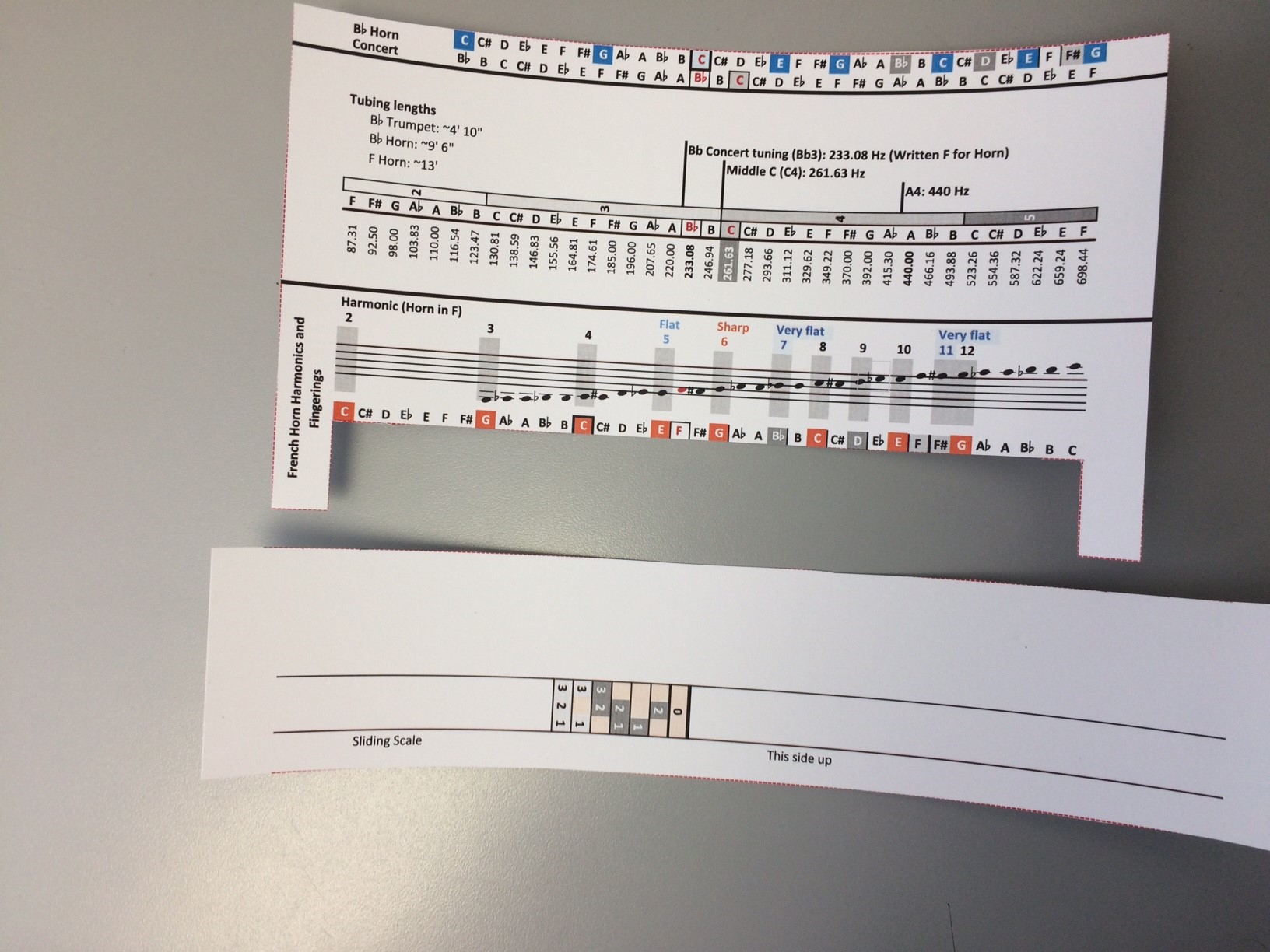

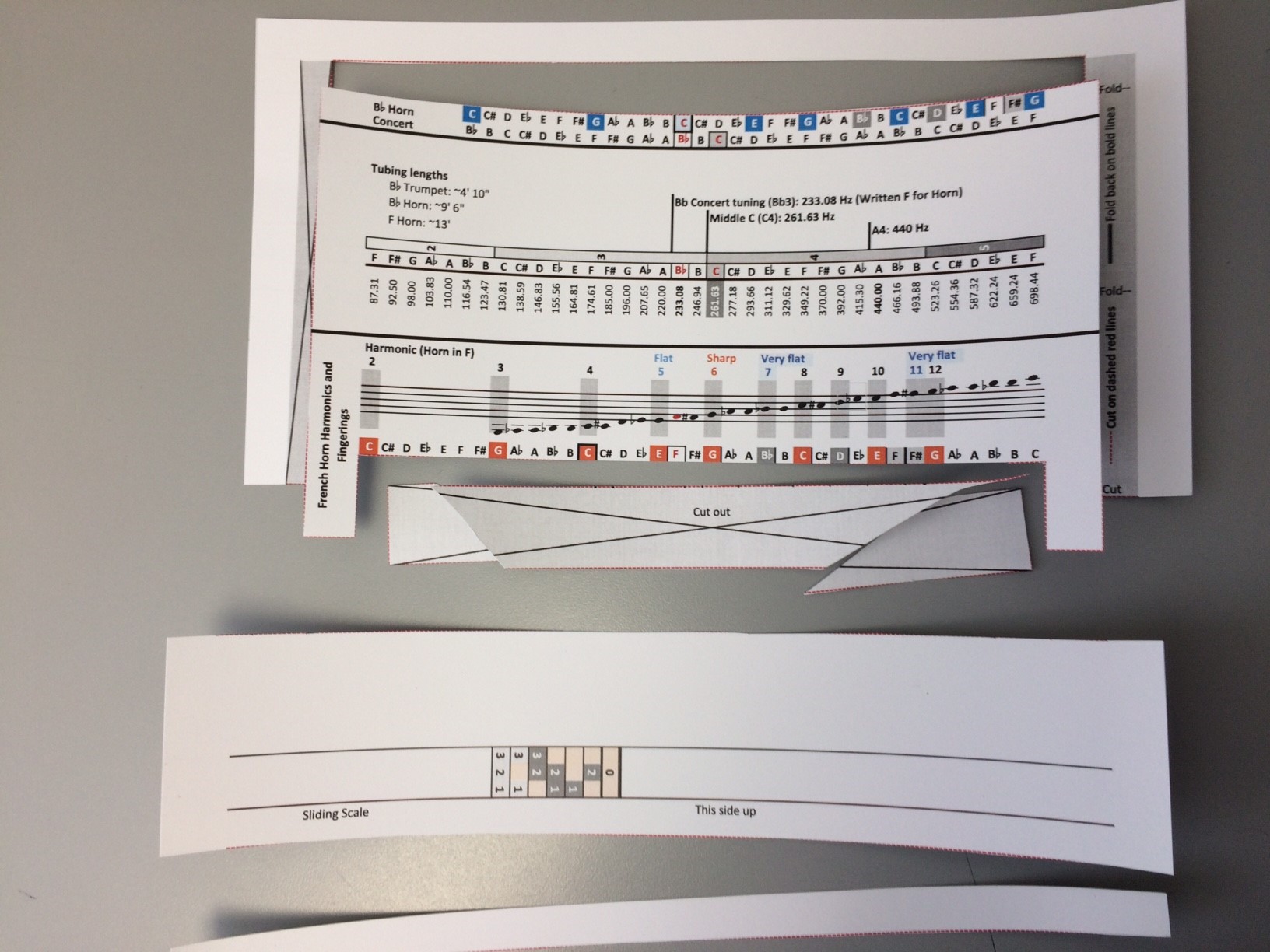

Things I wish I had known when I was learning the French hornThis tool is to help you (or your student) understand harmonics and fingering of the French horn. I've included a pdf file of a movable graphic you can use if you'd like. I have done another graphic for the Bb trumpet, but the French horn is particularly tricky because of the "partials" that occur because the harmonics are so close together in the range the horn is played.

Both of those are available in the Excel file here.

To start it helps to have a basic understanding of the concept of the harmonic series. There are a lot of good resources for this on the net, but I’ll just summarize the basics here as it relates to this tool.

“Harmonic series” isn’t as scary as it sounds. It's just the set of notes an open tube can play.

Imagine the long, straight horns the guards at a medieval castle (or angels) would play. They don’t have valves so they can only play certain notes. You can actually grab any long tube (like the hose on a shower massage—really!) and play those certain notes. If you take that long tubing and roll it up so it’s easier to carry you have a bugle. That bugle can’t play all the notes in a lot of tunes—just some intervals. Think Taps, or Reveille, or the kinds of things you hear a bugle play.

Again, the notes that an open tube plays are called the “harmonic series.”

To play the notes in between those tones they installed valves. All a valve does is to route the air through another length of tube to make the overall tubing longer. The longer a tube is the lower the tone it plays (it basically shifts the harmonic series lower). The middle valve shifts the note 1/2 step lower, the first valve shifts it one step, and the third valve shifts the note 1-1/2 step lower. Combinations of those add up. So, for example, the first and second valve drop the note by 1-1/2 step.

2 -.5

1 -1.0

1,2 -1.5

2,3 -2.0

1,3 -2.5

1,2,3 -3.0

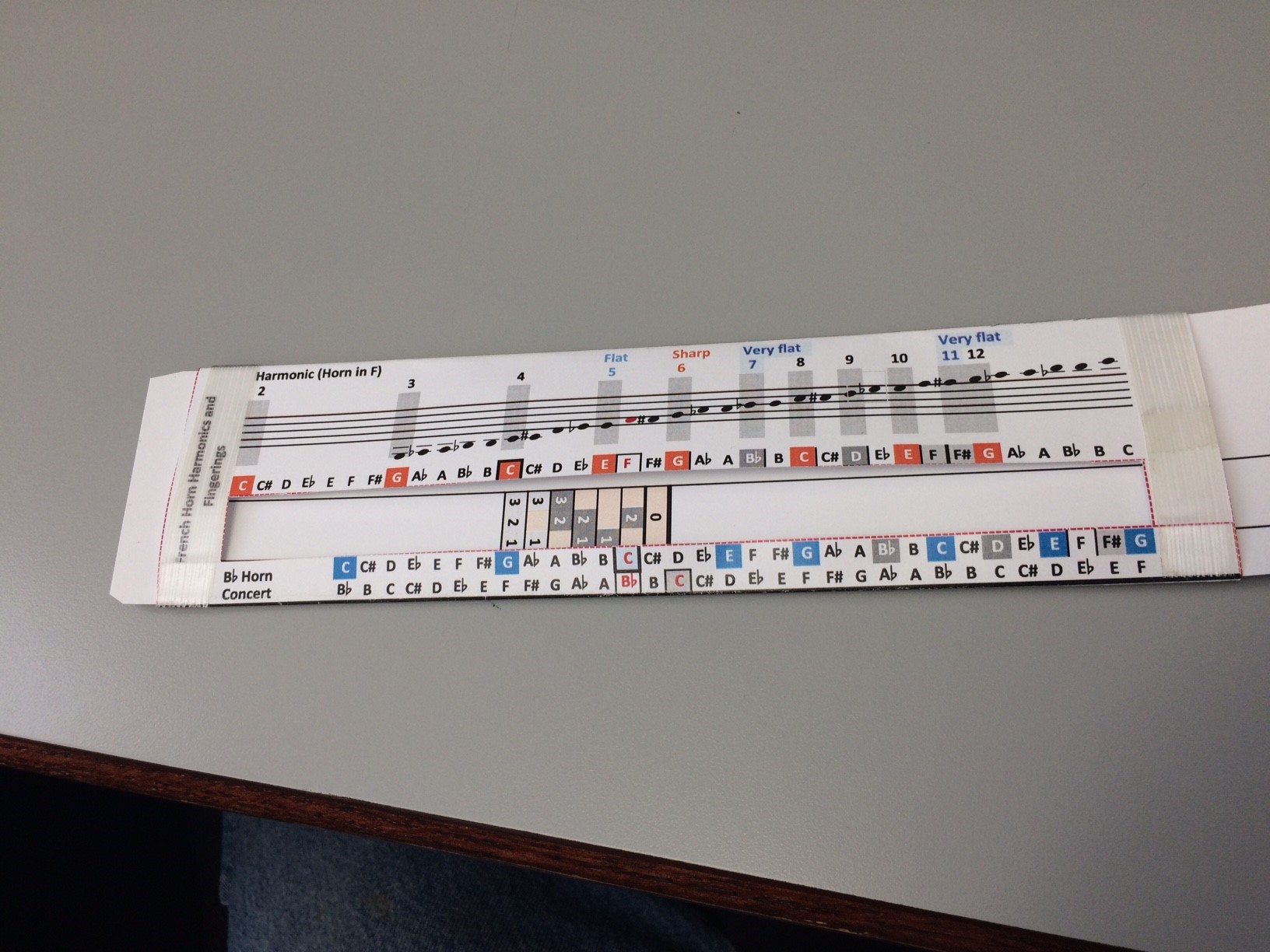

Those steps are represented by the blocks on the center part of the graphics below. The first one is open, then (moving to the left, down the scale) middle valve, first, and so on, as valves are switched to lower the pitch of the harmonic.Using the toolFor example, with the open (0) block aligned with the E (5th partial), the pitches go down from there with the valve sequences as illustrated below. You know all this. But typically you would start from C and go up. What I didn't take time to understand when I first learned to play (the trumpet) was that when moving from C (open) to D I was jumping up to the next partial and lowering the pitch with the valves (I wasn't raising the pitch from C with the valves).

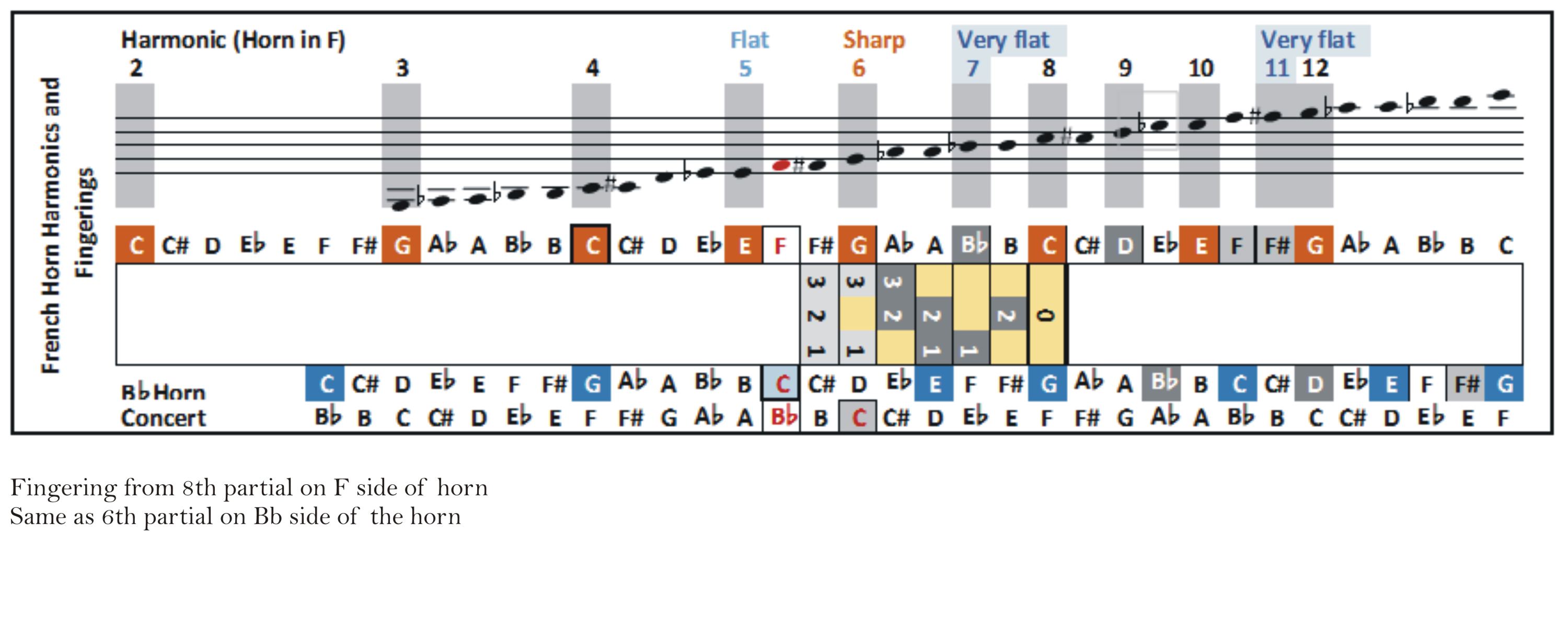

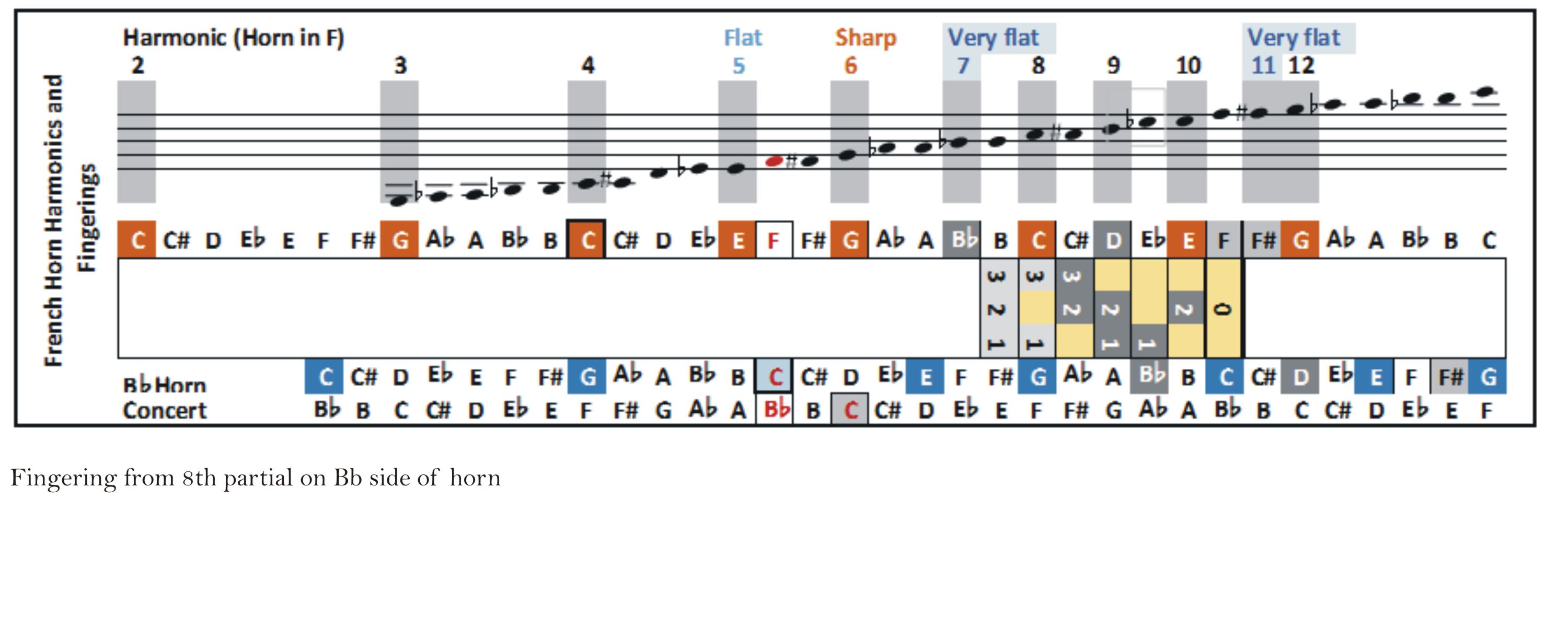

Next let's jump to the 8th partial, C. You can see how the fingerings go down from there, same as from any other partial. But here's where it gets interesting. If you are playing C and push the thumb key on a double horn, the note doesn't change. But you are in a different partial on the Bb side. With the open index on the 8th harmonic on the F horn you’ll see that it lines up with the “G” on the Bb side.

I hope this helps graphically illustrate what’s happening as you move from one harmonic (partial) to another. By seeing how the Bb side of the horn relates to the F side you can see why the fingerings are the same in that magical area from G#/Ab up to C.

Typically beginning at that Ab you start playing the Bb side of a double horn, and in that register it's easy. The fingerings are the same.

Until you move to C#.

Now notice that you jump up to the next partial, so instead of fingering C# as 1-2, you finger it as 2-3.

With the index aligned at the next harmonic on the Bb side and you’ll see why they aren’t anymore. You’re basically playing the fingerings that you would be if the “C” were a “G.”

I hope this graphic can help to make sense of why certain pitches are coming out of your horn. When I first picked up my double French horn I was lost. I played it in the store and I could get the tones out of it, but the notes made no sense. I could play intervals of a second without changing fingering. I paid for it and left having no idea what notes I was playing.

The first trick with getting your bearings is that the music is notated a fifth higher than concert pitch, so when you're looking at a note on the music you're not playing a pitch you might expect. Then you have the partials. Oh, those partials. Throw in a thumb key that sometimes changes the pitch and other times not . . .

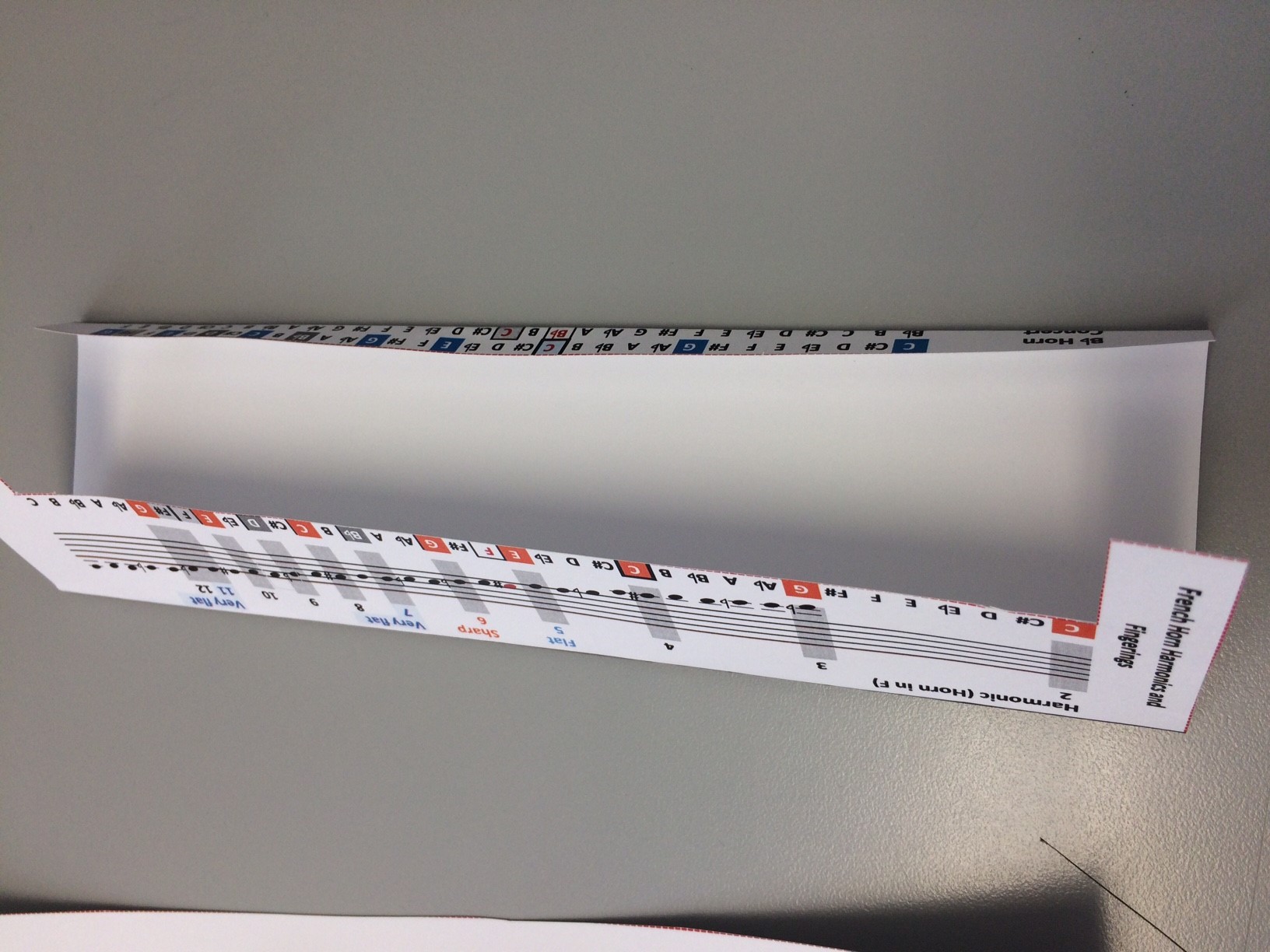

Print the pdf file on card stock.Cut out the gray areas and the slider (red dotted lines)

(Click on image for full size)and fold on the lines where it says (heavy black lines). You're folding the envelope (stationary part) around the slider. Secure the outer envelope with tape or glue.

Secure the outer envelope with tape or glue.

You might want to trim the ends of the slider and bevel the corners a little.

(Only don't use ugly filament tape like I did)The notes that are highlighted on the stationary part of the tool are the notes in the harmonic series. Those are C, G, C, E, G, (Bb), C . . . Notice that they get closer together as the notes get higher. We’ll get back to that. F has a block around it because it's the Bb concert tuning note (C is blocked out on the Bb scale).

To use the tool align the “open” block in the sliding scale with a harmonic on the fixed scale. The other blocks will show the fingerings for the notes as they go down from that harmonic.

Now, you’ll notice that as you move the slider up and the harmonics get closer together, the fingerings cross lower harmonics. That’s why a French horn is so tricky. It basically starts on the fourth harmonic whereas a trumpet starts on the second. It’s harder to know exactly which note you’re playing (especially since, as I mentioned, the Horn in F is tuned a fifth off concert pitch so your ear isn’t as helpful to locate where you are).

To save space I’ve only noted one naming of the black keys (Ab, C#, etc.) and I’ve gone with the version that’s closest to C major on the circle of fifths.

I’ve made notations to show which harmonics are flat and sharp. The 7th is extremely flat and the 11th is worse than that. In fact, it falls between F and F# on an equal temperament tuning.

On the back of the fixed scale I’ve put a chart of the frequencies of the concert notes . . . just for reference . . . in case you’re interested. The numbers above the note names indicate the octave. For example, Middle C is “C4” and the 440 Hz A is call “A4.”

I know, I know, I should be putting my effort into putting this all on an app instead of something you cut out of card stock.

If you care you could open the native Excel file that I made the .pdf file from and mess around with the relationships there.

How Low Can You Go?

I keep emphasizing that the valves lower the note. I guess I'm embarrassed I didn't think to notice that years ago. So when you play open C and move up to D, you've jumped to the next register without knowing it.Okay, so if that's the case, why can't I just keep easily going down from the lowest register (C) until all the valves are pushed? I have a really hard time getting below C on my French horn (and all the fingering charts just keep going into the basement for another octave from there).

I guess the longer tubing is just different from a physics standpoint, because of the bell and mouthpiece being optimized for a certain range. That's why a horn is in F--it's the length of tubing they figured out had the most pleasing tone.

That also speaks to the two sides of the horn. When I first figured out what a double was I figured you just played in one key or another. Like, I could read off the tenor sax music from the guy next to me. Interesting, but I don't know why you go to all that trouble to merge two horns into one.

The gal who used to play next to me in the band was really good. I kind of looked to her for tips and tricks. And she kinda convinced me to use the Bb side of the horn from Ab up. So I looked into it some more and found out that those notes play better from there, the Bb side is a slightly different tone . . . if you care you already know all this.

General Notes on the Devices

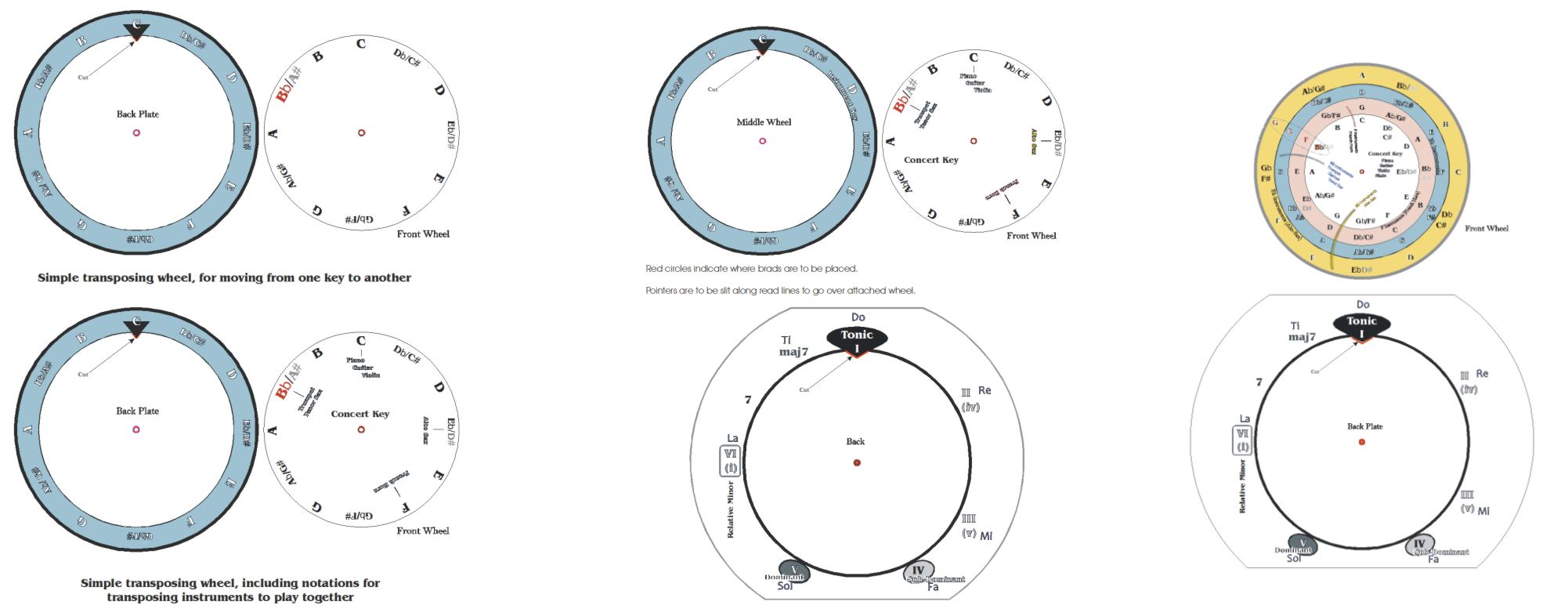

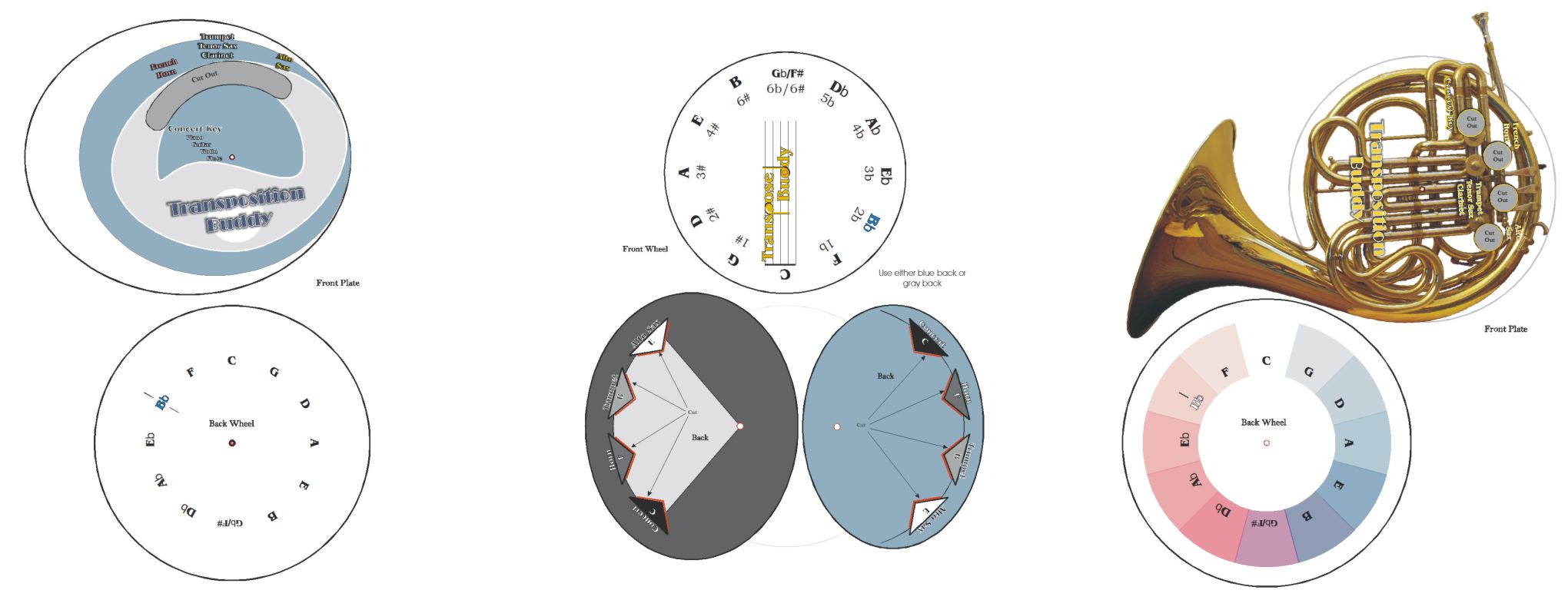

The resources here are stuff you print out on card stock, then cut out and put together. Like we used to do. Before we learned how to do it better electronically. I sometimes find that holding something in my hand is illustrative, like with the circle of fifths wheel, where you can see everything right there. I'm sure there are some good apps that illustrate it just as well; I haven't looked.There are three basic kinds of these gadgets on this page:

- The fingering guide, which is a horizontal slide, and

- The transposing wheels, of which there are two types.1. The first type has notes arranged as they are in scales. You can use that for direct transposing--if I move from the key of F to Bb what does each note change to? I have three types of those, a simple wheel, one that transposes by instrument with two wheels, and one that has all the instruments in their relationships in a single center wheel.2. The second type arranges the 12 notes of the chromatic scale in a circle of fifths. The purpose of that is to group all the instruments together and relate them to each other. Those wheels are useful to relate instruments, for example, transposing instruments in a band or orchestra. For example, if you have some friends over and a concert breaks out, you can see what key everyone has to be in to play off the sheet music you're using on the piano.

This actually happened once. Coolest thing ever. My kids had friends over, we had a guitar out in the living room. Someone asked if they could play it. Someone else joked that I wouldn't happen to have a sax. I said "As a matter of fact" and went downstairs and came back with a sax. After a few trips downstairs we had a room full of people playing guitar, piano, sax, tenor sax, violin . . .You can use the circle of fifths wheels to visualize "if the violins in the orchestra are playing a certain key, what the heck key did the composer expect me to be playing in?"Like I said, coolest thing ever.

If cutting out all these deals on card stock is too much bother, you could try this transposing mnemonic. Just imagine the piano as flat and the horn as sharper, the trumpet sharper still, and the alto sax as sharpest as all. Then move sharp and flat around the circle of fifths as needed.

Those three different wheels that are laid out in fifths are essentially the same with different cosmetic designs. The one with two different backplates to choose from lets you see the whole cycle of fifths at once. The other two cover up everything except the four that you are using.

My story

When I was a little kid I started playing the trumpet in the grade school band. I sat down with my new (used) trumpet (cornet) and a fingering chart, and I started working out notes. I began with an open tone, then used the fingering to move up notes from there. I got fairly competent. I remember the day when I could play a full chromatic scale without looking at the chart.For a short time in grade school I played the French horn, because they needed a French horn, and it was, after all, just like a trumpet, right?

I played trumpet through junior high and high school and I got pretty good. I didn't play in any bands in college or after, but I kept my trumpet(s) and I continued to play them.

Fast forward 30 years.

I found out we had a local band that played concerts throughout the summer. I approached the conductor about playing in the band, but he already had a lot of trumpets (a lot of trumpets). One of us suggested the French horn. The conductor said he could use another one in the band, so I went shopping for a French horn. I found one that was a double—I had no idea that they came in any configuration other than the single F horn I played in grade school. I sat down in the store and tried it, using trumpet fingerings. Some of them made sense, but some were confusing. Sometimes I could move intervals of one step without changing fingerings.

Oh, well. I bought it and left the store having no idea what I was getting into. I'd figure it out.

I kept reading "The French horn is hard." Yeah, I remember it took a lot of air; I'd sometimes get light-headed playing it in grade school. Nuh-uh. I had a lot to learn. Pronounced "partials."

As a trumpet player I had a sense of the valves each changing the pitch a specific amount, since I saw fingering patterns repeat as I moved up a scale. But it was just a sense, not an understanding, like a cat that knows when he goes to the door when a human is around it opens. I never bothered to understand it. I never needed to.

I didn't perceive what was happening on an intellectual level, not even to the point of observing the obvious: that the valve lowers the note, rather than raising it. That's probably why it never clicked. It would have been obvious had I thought of moving down from open notes. But again, I didn't need to. On a trumpet you finger the note and that's what comes out.

So now I know.

Then someone in the band approached me about playing in an orchestra. Those of you who play orchestra music with a transposing instrument know what I'm about to talk about. The music they put in front of you isn't in the right key. Not only that, but it isn't in any key. No key signature at all. You either know what I'm talking about or you think I'm delusional and you're backing slowly away. Either way, there's plenty of stuff on the inter-webs about that if you care to find out. Fair warning: none of it makes any sense.

Point is, if you play French horn in an orchestra, you're transposing on the fly.

So . . . partials, transposing . . . all the useless nonsense you find on this page is a result of my journey to understand that stuff. I hope you find something helpful here.

Ha ha hah! Oh, geez, I slay me.

I'll Get to It

8.06.17

I know what you're thinking. You're thinking "Frank, why don't you turn all those little transposing wheels you've created into .pdf files that we can print off?"But I'm thinking. "Geez, how come my special fonts disappeared and the flat symbols show up as lower-case b, if they print at all, and why do the colors render differently in the PDF than when I print from the native software?"

And you're thinking "No excuses, Frank. We want to print stuff out on card stock and cut it out and put it together with brads and carry extra stuff around in our instrument case, instead of downloading free apps that do it better on a little phone we already carry."

Give me a break, guys. Being irrelevant isn't as easy as it looks.

Transposing Mnemonic

9.18.18

When I first had this idea I figured it was in the running for the dumbest mnemonic ever. But it's grown on me:

Remember instrument keys using the Circle of Fifths moving from piano to F Horn to trumpet to sax.You know when your friends come over and you want to make music together? It works fine as long as you're playing the piano and guitar and violin. And flute.

But when someone wants to break out a trumpet or sax or French horn, you have to transpose.

Some people can probably just do that automatically in their heads, but I'm not that bright. I have to think it through. So here's the mnemonic:

The piano is flat. Imagine a baby grand with the lid closed. The instruments are sharp. Imagine the ligature and reed of the alto sax. It's pointy. The trumpet is kind of pointy, but not as much as the sax. And the French horn isn't really pointy, but, work with me here, its shape isn't as flat as the piano.

For our purposes the piano is the flattest of the instruments. The French horn isn't as flat. The trumpet is sharper, and the alto sax is the sharpest of all.

So to transpose from concert (piano) to French horn you go sharp one step around the circle of fifths. The trumpet takes you two places around. And to transpose to the Eb Alto Sax you go sharp three places.

Same thing going back the other way. If you're moving from the alto sax to the piano you go flat, the other way around the circle of fifths, three places. Past the trumpet, past the horn, to the piano (which, as you recall, is nice and flat with the lid closed). The trumpet key goes two positions (around the circle) flatter than its notation to see what the piano is playing. And the horn key goes one position flatter to get to the piano.

Example, you're playing the French Horn, your music is in F, the piano is one step more flat: Bb. The trumpet sitting next to you is one step sharper: C. If you're playing the piano in Bb, the saxophone is three steps sharper: Key of G.

Okay, I know, the clarinet is a Bb instrument, too, and it's more pointy than any of them. And the Tenor sax is about as pointy as an alto sax, and it's in Bb, too. But we're just going to use the trumpet to represent all the Bb instruments. If it made perfect sense it wouldn’t win the prestigious Dumbest Mnemonic Ever award.All right, so it may be dumb, but it's not the dumbest thing out there. Look up instrument transposing on the inter-webs and you're going to get charts that list the concert, then the trumpet next, then horn . . .Then they're going to say "To transpose from concert to Bb move up one major first."

No. That's dumber than this mnemonic. This method gives an order to things; each step is the same interval.

Maybe thinking of moving one major step works if all you have to deal with is a trumpet, but what about the sax and the horn? Who's going to remember those intervals (especially since they're backward from the name)?

You are. You are, because you're thinking in fifths.

Think in fifths. Even if you don't use the piano being flat mnemonic deal, just think in fifths. Then the order and the intervals are clear. Trumpet isn't next to the concert pitch, even though it seems like it's closest (Bb to C). It two fifths away. Move in fifths.

Did I mention move in fifths?

(And I love how I get all "That's dumb!" about charts written by music educators who have forgotten more about music than I'll ever know. I could have just as easily said "I wonder if there's a better way to organize it in your mind." Eh, I'm a schmuck.)

Or you could just print off this handy little transposing gadget and keep it in your piano bench. Or instrument case. (Or find an electronic version for your phone created by someone more hip than this guy who still doesn't own a pair of brown dress shoes or skinny jeans.)

But if you're looking for something you can carry around in your brain, try this little mnemonic. It works for me.

I've done another explanation of the technique on this page with a chart.

The Missing Brass Link

I know you probably think about this as much as I do. Transposing instruments.So you pick up your Bb trumpet and you look at the fingering chart and you play a C major scale. Cool. But then when you play with the piano you have to have a separate piece of music. 'Cause the C on the piano is a different note than the C on your trumpet.

That's 'cause you've got a Bb trumpet, meaning when you play a C it comes out as a Bb really. Your buddy who plays the Eb alto saxophone blows a C and it comes out as an Eb--a concert Eb (meaning what the piano plays).

Well, it's nice of the guys who write the music to have the elementary kids learning the C scale for their first notes. Save explaining all that sharps and flats stuff in the first lesson. When they blow a note without pushing any valves you just call what comes out a "C."

But the saxophone's open note is a C#. It doesn't have an open note on the C scale. Yes, but it does have a complete sequence of fingering that makes logical sense that they call the C scale.But I'm like you. I always just wondered about the possibility of teaching from the get-go that the note you're playing is a Bb. So the new player looks at the music and the scale he's playing when he starts with an open note has two flats in it. If you don't want to teach him sharps and flats you just teach him the concert C scale which starts with a fingering that's not open and is the scale that in the current system has two sharps. But the music he's looking at has no sharps or flats (which is what he's playing, really).Oh. You mean like the trombone?

The trombone is the missing link in transposing instruments. Because it's not a transposing instrument. The common trumpet or cornet is a Bb trumpet. The most common trombone you see is a Bb trombone. Oh. Just like I explained, right? When you blow an "open" note, it comes out a Bb.

It does, but you call it a Bb.

Isn't that crazy?! (Maybe I'll tell you the "Isn't that crazy?!" story sometime)

And you notate it as a Bb in the trombone music.

So the first notes a kid learning the trombone learn are a Bb and an F. He's just stuck with the fact that when the slide is all the way in the note he's playing has a flat on it (well, not if it's an F, obviously, but it's still not a C). And even though it's called a Bb trombone, it plays the music in the concert pitch like the flutes and the pianos do.

I guess it's because every note on the trombone is "open" since you don't have any valves. But . . but . . . you still have a standard default kind of position (I forget the musical term—they use it to describe which side of a French horn plays without the thumb valve, maybe base or something).

Next week's question we'll just never know, why did they start on a "C?"

Harmonic Series, Redux

To illustrate the extent of my cluelessness . . .Early on in my trumpet playing career I learned that you could hold down the first valve and play reveille. Then I learned that I could hold down the first and third valves and play taps.

Uh . . .

Yes, you are correct, I could play either of those (or mess call, or to the colors, or a fanfare, or any bugle tunes) with any combination of valves or no valves at all.

I guess the purpose of this is just to show how I didn't understand that all a valve does is make the tubing longer and shift the harmonic series. I guess I just figured the whole valve thing was some magical deal that supernatural beings had bestowed on earth and then departed, leaving us a magical technology that was beyond mortal understanding.

Still . . . there are low tones on some of those harmonics (1-3, 1,2,3) that aren't as accessible as the same position low tone in open position. So this mortal still doesn't fully understand it.

Oh, well. I guess it's like women or color TV. You don't have to understand them to appreciate them.

More Trombone

In an earlier Chautauqua we talked about the harmonic series as it relates to the French horn, especially the fingering on a double. Today let's climb on the motorcycle and chat some more about that.The gadget I put together to visualize that is an aid to why certain fingerings yield certain notes. The danger of laying it out all neat and tidy like that is that it gives the impression that when you hit that fingering in that register you get that note. Like striking a key on the piano.

Well, you can't play the French horn very long before you figure out that's not the case.

The device (gadget, graphic--I need a good word for the dealy flopper) does hint at a couple of reasons that is not the case. First, I've indicated places where the partial (or register) is flat or sharp. So all of the tones down from that will be slightly that way.

Next, notice that there is a partial on the seventh harmonic that's notated as Bb. It's called out as "very flat." But t we just gloss right over it, like it's not there. We can finger Bb as open on the F side, and it follows that we can finger everything down from that partial the same way we do any other.

But we don't. And that's what this Chautauqua is about. Hold that thought.

Every brass player should pick up a trombone and mess with it at some point after they become somewhat proficient and in preparation to being very proficient. The trombone is just a tube; no valves. But it's a tube that changes lengths, so it's a great illustration of what happens when you pipe flow through valves on other brass instruments.

Here's the point (and not a minute too soon!). When you mess with the trombone without knowing the slide positions you have notes you try to play that don't sound any note at all. I'm not saying they sound the wrong note, I'm saying they don't make any note.

Let's illustrate with an example. You're working your way up the scale without consulting a chart, you play, say, a first position Bb, then you want to move up the scale, so you put the slide out there and play what you want to be a C. And it doesn't really make a note.

You hear the note in your head, and you're playing it with your lips, but the slide is in the wrong place. So what you get is a sound that's not a note at all.

There may be a metaphor there . . . a situation that is not right and you know it's not right but you're trying to force things into place . . .

This may be something you have to try on a trombone to visualize. What's happening is that your lips and brain know the note and are trying to force it. It's not like a key on a piano. It doesn't just come out as a note that's wrong. Your lips and your brain won't let the tubing alone determine the note. They are trying to make a certain pitch, and the tubing length is fighting that.

So now we get back to the French horn. Still have that thought I told you to hold?

I said that trying to play a note with the wrong slide position is not like striking the wrong key on a piano. For that matter, it's not like a note on a trumpet, either, where you hit the wrong fingering and (in most cases) you just get the wrong note. But you may have discovered, as I eventually did, that a French horn is not a trumpet.

On a French horn your lips and brain--and your hand in the bell--do a similar thing to what's happening on the trombone and try to force the note. In some cases on the French horn you can actually play a note you're trying to hit with the wrong fingering.

So that's what happens with the deal I mentioned about moving up from C the first time you picked up a trumpet. You picked up the trumpet, looked at a fingering chart, and blew a C. No valves. Open.

Then you saw that D was 1-3, you pushed down the 1 and 3 valves, and you blew a D. That was up one note. Then you blew an E. All this was moving up from C. Then up to an F, faithfully following your trusting fingering chart.

The next open note was G, and you were aware you had to bump up to the next register.

Only you didn't. You were already in the next register starting with D, and didn't realize it. Your lips just automatically took you up the scale because your brain knew the next note was higher.

Isn't that crazy?!

Anyway . . . if I had a point somewhere I've forgotten what it is. I guess that the gadget is a guide. You understand that the pitch of the note on a French horn is kind of a fluid thing.

All right, I'm going to settle back and enjoy the motorcycle ride (vague reference to "Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance," the book I linked to above where we learned about Chautauquas). You do whatever you're doing.

Singing

Just some more ramblings to try to explain what I'm talking about.When you sing you don't think about a fingering for the note. You sing the pitch and it comes out.

Well . . . it used to. Now that I'm old it's a craps shoot whats's going to come out.

Point is, you set the pitch with your vocal chords without thinking about the mechanics of what's happening.

What I was talking about with the trombone is that you're trying to do the same thing with your embouchure. So your lips and your brain are making a note, just like when you sing a certain pitch, but the tubing you're blowing through only allows certain tones.

If you've tried it, you know what I mean. You'd think that you blow and a note comes out--whatever note the slide position dictates.

Not exactly so if your brain and lips are trying to force a certain note.

Anyway . . . I guess we're done here.